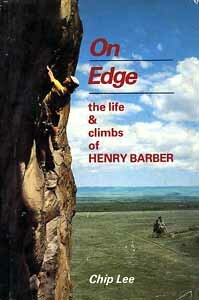

On Edge: The Life & Climbs of Henry Barber

by Chip Lee, with David Roberts and Kenneth Andrasko

Appalachian Mountain Club, Boston, 1982. 291 pages, black and white photographs

“Hot Henry, Little Henli, Harley Warner...no matter what we call him, Henry Barber has been one of America's most visible and influential climbers for over a decade. In the preface, Dave Roberts refers to him as "a climbing genius" and, despite the hullabaloo about the Breach Wall accident, the claim sticks. “Hot Henry, Little Henli, Harley Warner...no matter what we call him, Henry Barber has been one of America's most visible and influential climbers for over a decade. In the preface, Dave Roberts refers to him as "a climbing genius" and, despite the hullabaloo about the Breach Wall accident, the claim sticks.

A complete list of Barber's first ascents, first free ascents, first all-nut ascents, and on-sight solos would be amazingly long. Barber combines a high level of skill with fanatical drive and a powerful sense of ethics and style. This bio picks up with Barber's first climbs, at age 15, and follows his career through to his second trip to Dresden, in 1979.

Squeezed between those dates sits a lot of climbing, and the book keeps track of the major developments for each year. (…)

And the mechanics of the book? Frequent quotations from interviews with Barber and about 100 photos, which is good. In general, Lee writes best when the action is thickest. The hard solos..racing night and day through the Australian bush...AI Harris and Henry Barber driving Paul Trower to the hospital at 90 miles an hour on a crowded two-lane road...at these times your pulse picks up and Lee's prose clips along. Other passages of the book do not work as smoothly. More than once sentence order is odd, descriptions cliche, or the overall unity breaks down. (…)

If you have any interest in American rock climbing, check this book out; the subject makes up for the form. If nothing else, it should inspire you. Three hundred twenty-five days...shit, with good weather, you can beat that...”

Charles Hood, „Climbing” 1983, April, No. 78, p. 48

“At age 28, Henry Barber makes a problematic subject for the biographer. Many of his achievements are difficult to dramatize: short rock problems rather than the evolving alpine adventures that books are more often made of. His most arresting climbs have been solo efforts that place a burden on Barber's own powers of narration. And at the center is Barber himself: can he be as interesting as his accomplishments? The preface to On Edge terms him a "fascinating character"; the book unfortunately fails to substantiate this claim. (…)

David Roberts' preface acknowledges that some readers will find Chip Lee "too close, too uncritical" for accuracy. The problem is that he is indeed too uncritical, despite serious efforts not to be, yet finally not close (or penetrating) enough to illuminate Barber's nature, which emerges as opaque rather than mysterious.

Lee provides some lively characterizations, such as Dresden's Bernd Arnold and the late British wildman, Al Harris. Henry Barber is one of the less vivid people in the book. Whether because of reticence—Lee's or Barber's own?—or literary misjudgment, a number of areas of interest are merely touched upon. (…)

Although afflicted with many shortcomings. On Edge recounts some stunning achievements from Yosemite to England, Dresden, Australia and Turkestan. I failed David Roberts' sweaty-palms test ("I doubt that there is a climber in the world who can read some of the episodes in Chip's book . . . without having to pause to wipe his sweating palms on his trousers."), but other hands may respond more readily. The book is of importance for those who follow the frontiers of hard climbing. It establishes or confirms Barber's significance in several areas: his insistence on good style, ability to lead on sight climbs that had stymied locals, and his extraordinary solo ascents.”

Steven Jarvis, “American Alpine Journal” 1983, p. 322-324

“Henry Barber will almost certainly be remembered as the outstanding international rock climber of the 1970's. I say rock climber because, with respect for his adventures elsewhere in the mountains, it was on rock that Henry made his mark. Henry's rise to fame coincided with the development of rock climbing as a separate sport distinct from mountaineering. It was the beginning of the era of the Rock Jock, a means to an end in itself. An expanding climbing media headlined major rock climbs, and the national media in many countries began to take an interest. Opportunities to star became more numerous. From Yosemite to Yorkshire, new names began to emerge with almost every issue of Mountain, young climbers keen for recognition, but too often without regard for methods or ethics. The codes for the sport were not as universally accepted as they are today, and frigging was only in the eye of the beholder.

Henry arrived on the scene with a no bull shit attitude. Yo-Yoing, pre-placed runners, resting, inspection while cleaning and numerous other practices were abandoned by Henry in favour of a "do it clean or fail" attitude. He became an international marker of performance and behaviour both on and off the crag. He forced climbers, particularly in the English speaking world, to reaccess their climbing at a time when cheating and disputes were beginning to shake the good humour at the heart of the sport. When, as in Dresden, Henry discovered a code of climbing superior to his own, he worked hard to master it. If he failed the first time, he usually went back. Chip Lees book contains all of the ingredients of Henry's life, but fails to put them together coherently. We have, instead, a series of reminiscences and anecdotes transcribed from endless taped conversations with Henry. Many tales will already be familiar to climbers who followed Henry's exploits in the seventies, but may be interesting enough to someone discovering Henry for the first time. (…) Another major failing of the book is the lack of basic biographical grit to help us understand Henry as a character. Of his own admission, he is not a great natural climber. His ambition and fifty weeks a year approach to climbing brought him results and tell us something about his New England upbringing. But like most puritans, Henry balanced his virtues with his vices. Riotous Thanksgivings arrived just about every day of the year when Henry was in the mood. (…)

To its credit, the book is very amusing in places and gripping in others. A lot of time has obviously been spent in an unsuccessful attempt to make it stick together. Some statements contain a refreshing intuitive accuracy: "Henry had created an image and a place for himself in which he could not afford to flounder or fail... in a way, Barber had always been the producer and director of the story of his deeds. He has always thought of himself as being in a movie, standing back to watch himself climb ... in the process (he) has become his own historian." On this occasion, Henry could have done a much better job of producing and directing.”

John Porter, “Mountain” 1983, March/April, No. 90, p. 48

|